Running my science lab like a startup for a year

Todd M. Gureckis · · 10 minutes to read

Science can be a lonely enterprise, particularly for graduate students who are primarily working on smaller projects rather than on several things at once. I often hear that relative to grad school, working in industry feels more like a team effort with co-workers with clearly defined goals/deadlines.

However, within a science lab, the relationship between the lab PI and students is complicated by the fact that students are, well... students, and are working on their classes and degree, learning while they are mentored. Students are expected to "lead" the projects in their dissertation, with highly variable lengths of time for a project. This leads to a spoke and hub model where each student meets regularly with the PI who has visibility of all the lab projects but between students communication can be spotty.

Instead, of this hierarchical model, our lab decided to try operating with a common purpose for a semester pretending to be more like a small startup company trying to survive in a competitive market.

To do this we adopted common practices for project management from industry (e.g., Agile software development/Scrum) and applied them to not just our code but our overall goal of running a scientifically productive lab. We're certainly not the only or first lab to do this but I thought it was an interesting enough experiment to share.

Background

Before starting this experiment I discussed the broad outlines of my goals with other faculty and students several times. The issues facing the lab were:

- a feeling of social disconnectedness following several years of pandemic remote work

- a diminished lab culture (partly due to a large number of people leaving/joining in the pandemic)

- a desire to scramble the status quo of running a lab

- a feeling like we were being less efficient than we could be

In response, I began thinking of changing how I viewed my job as a PI. Most commercial software development is based on products (e.g., shipping a new software project). However, running a lab has different goals and structures. What is the "product" of a lab? Perhaps it is to create new research with high ethical standards, write up the results of that work so the public can understand it, provide training opportunities for students, and obtain new sources of funding, among other administrative tasks.

I started to imagine the lab as being a startup that does these things and tries to do them well [1].

So instead of viewing things hierarchically -- a PhD student is working on a project mentored by me, I started thinking of it as "student X and I are trying to create this new feature/product" or "I need help from postdoc X to keep the lab running well for our customers (funding agencies)", etc... This turned everything into more of a common purpose because even if a PhD student was spending a week reading literature they were helping to move the overall lab "company" forward in some sense.

One obvious source of inspiration was the type of effort my lab typically engaged in before conference deadlines. During these periods there's a clarity of focus and energy. The frequency of meetings increase. Students are working at their desks more and are discussing problems, asking for help, etc... I started to wonder why we can create a focused effort in those weeks and then the rest of the year things feel sometimes undirected/scattered. Could we not create for ourselves several "conference efforts" per year or semester even if there isn't a deadline that applies equally to everyone in the lab? So that's basically where things started.

With this general idea in mind, we undertook a semester-long project to reframe the way that our lab works. The key elements of this semester-long experiment were:

- Initial planning, democratic buy-in, and dealing with anxiety

- Two-week long "sprints"

- Socially accountable globally visible to-do lists

- Regular meetings to check in and provide accountability

- Daily registering of goals for the day

- Multi-week "backoff" periods for undirected exploration

I'll explain each of these in turn and I think anyone thinking of running a similar experiment could certainly pick and choose from this menu of ideas.

Initial planning, democratic buy-in, and dealing with anxiety

One of the first challenges of making a change in how people work is convincing people to take part. It is easy enough for a PI to announce "we're doing something new" but much harder to get genuine buy-in from everyone. Originally I started fielding the idea of having organized "sprints" (one to two-week periods of focused work, similar to the CogSci deadline) several times in a semester. Several students expressed some reservations about this idea. One concern was that this could increase pressure and feelings of lack of progress, create a negative level of competitiveness in the lab, or cause anxiety.

To avoid that we had many open conversations about the goals of these efforts. Everyone was given space to discuss their reservations as well as ideas about it. The first focused effort was scheduled for several weeks into the semester so people had plenty of lead time/heads up. Overall people had some reservations, but most were willing to give it a shot. I sent around a (semi)-anonymous survey ahead of our first sprint to gauge people's feelings and mostly they were good to mild. One interesting comment was that the very effort to plan the sprints and define them had increased communication and trust between lab members as people tried to define the goals of what we were doing and how it fits into their personal research goals.

In the end, the key was convincing people that this was about personal accountability and not about comparing people. It also helps that I generally don't have a highly competitive lab culture and don't usually foster that dynamic. So in the end people were willing to put aside anxiety about working in a more public way in favor of the perceived benefits which were mostly around social accountability and feeling like working towards a common goal.

I did talk to some grad students (not in my lab) at conferences that felt it might not work for them, and that the stress of being open about what you were working on (or struggling with) might make things harder but I think probably no one system works for everyone. So we pushed ahead with our experiment!

Two-week long sprints

The main component of our effort was to divide the semester into a series of two-week "sprints".

In agile/scrum development, a sprint is a set period during which a specific set of tasks or goals is accomplished. During a sprint, all members of a team focus on accomplishing as many tasks as possible. It is a focused period of work where other considerations are pushed to the side temporarily.

Sprints can have varying intensity but in our lab, the idea was that during sprints people were expected to be in the office more often (helped by there being breakfast some mornings provided by the PI). Also, we encouraged people to not schedule vacations or holidays during the sprint. We also expected and discussed the idea that people should decline some social or academic activities during that time (e.g., going to lunch with a fellow student) along the same idea as "Sorry, I'm working on a big deadline right now." Of course, life intervenes, people have to go to the doctor or meet family and friends who come from out of town. So the rules were not strong but just guidelines to highlight want the difference in intensity should look like. People were explicitly not encouraged to work extra late or on weekends. The goal was to foster the same singular focus each day during normal hours (for the individual, as some people prefer to work late) we often find during conference crunch periods. In the first sprint, we also planned check-in meetings at 9:30 am with the idea of emphasizing an early, focused start to the day. To start with we planned three such efforts distributed without 2-3 weeks pause between them.

The first sprint started fairly intensely, and even I was looking at my to-do list and feeling my heart race a little about if I was being effective or not. Of course, some of the anxiety diminished as the two-week sprint went on but the regular meetings about the sprint largely kept people on the same page.

Some issues that came up were that it was hard to universally avoid some things like vacations, big homework assignments for certain students or other classwork type things, varying emergencies like grant reports being due, etc... This isn't an issue though since it only affects one or two people at a time. The early meetings were not popular in part because of commuting time in the mornings so we abandoned those as the experiment continued. Also, we decided to reduce it from 2 weeks to 2 weeks minus one day so that the sprint ended on the final Friday of the period and we had a lab meeting with pizza to celebrate the end of the period and to discuss what people accomplished/learned.

Socially accountable, globally visible to-do lists

A key component for organizing these sprints was a socially accountable, globally visible to-do list. There are various software tools you can use for this but we went with GitHub Projects (Beta).

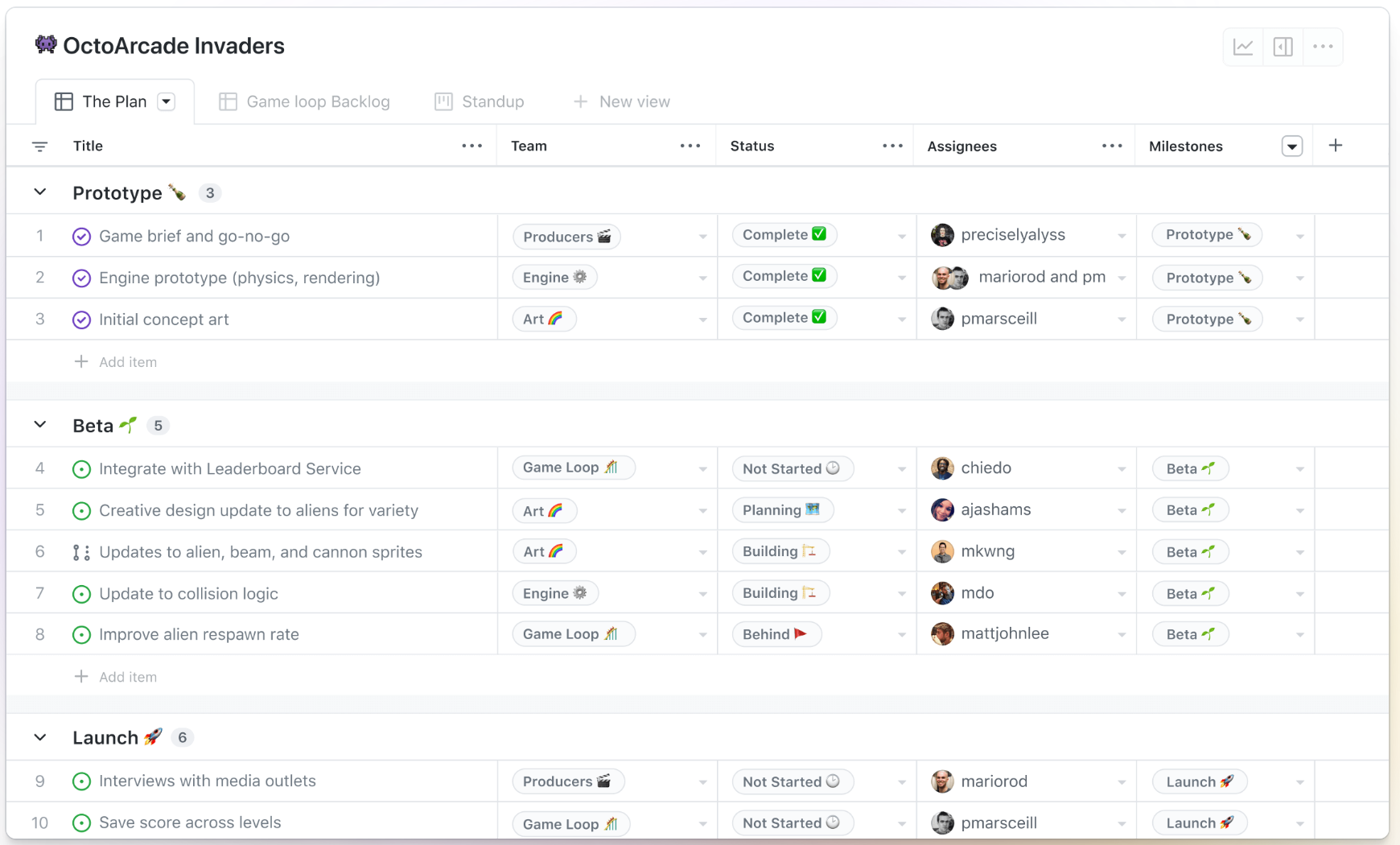

GitHub projects is a new (Beta) product from GitHub to help teams manage software development projects. At a basic level is it like a simple spreadsheet. Each row in the sheet is a to-do item, and each can be associated with various customizable fields/metadata. Here is one view of the system taken from Github's project advertisement pages:

Here the items are grouped into feature categories (Prototype, Beta, Launch, etc...) but the grouping is flexible. For example, you can create views of the data grouping by Status or who is responsible/assigned to the item. We simply created items on this spreadsheet and adopted some customized fields to help organize them.

GitHub Projects deeply integrates into GitHub as well so these to-do items can be tied to specific issues associated with a GitHub repo. For several projects now we have been using GitHub Issues as a way to track to-do items on our science projects. This has several advantages including that issues can be closed automatically by committing code to GitHub. However, you can also create to-do items that are not tied to a software project. For example, I created a special repository called "Todd IRL" (IRL = in real life) and added issues to that repo that were not software-related but were things I needed to do like submit a form or attend a meeting. This way all aspects of the lab could be managed in one place.

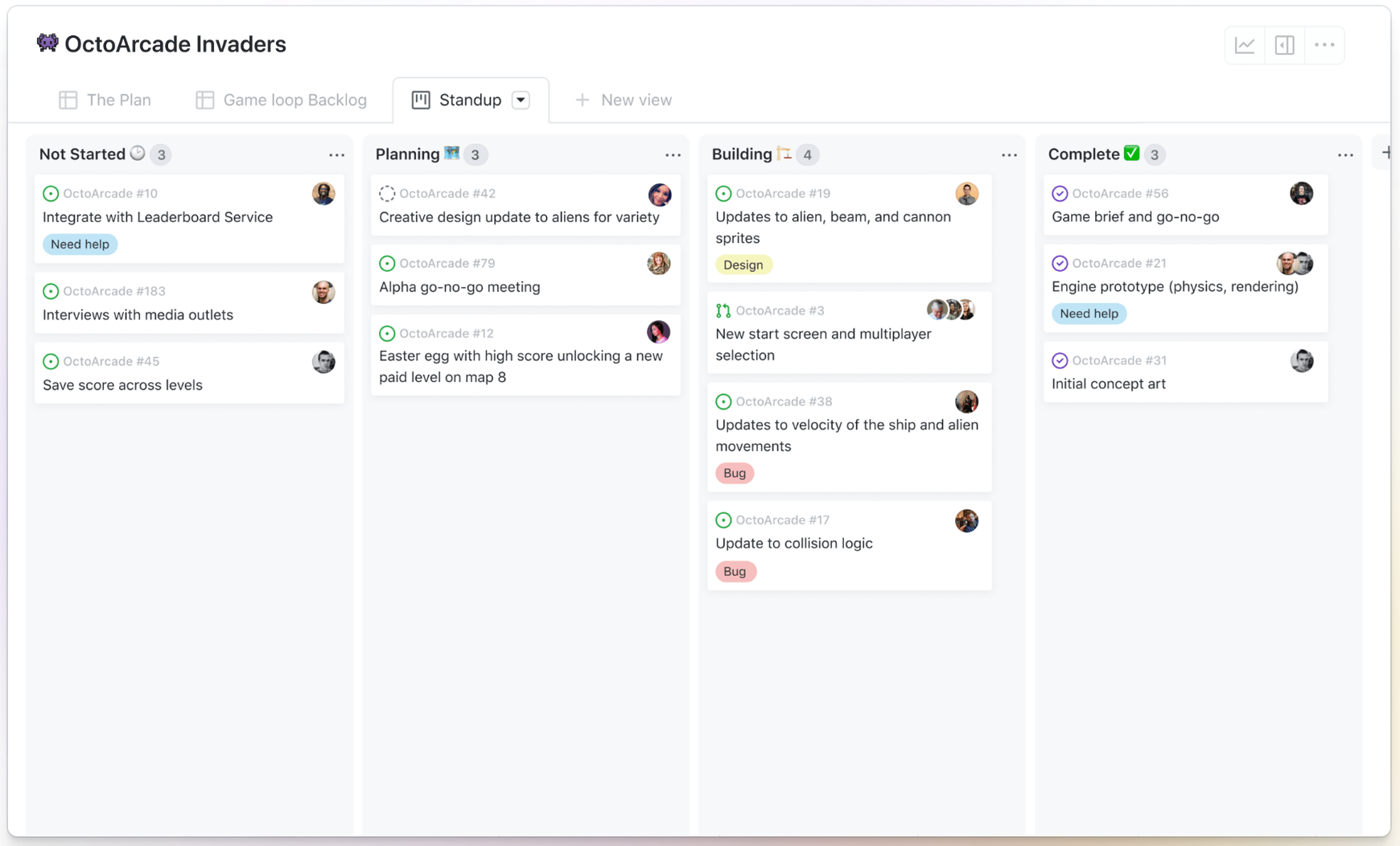

GitHub Project also allows alternative views including the popular Kanban board style:

Overall, we didn't do an extensive amount of research comparing products for group todo lists. The key was that we already use GitHub pretty extensively in our projects and the new Projects (beta) system did what we wanted.

The more important part (besides what software to use) is to-do lists are globally visible to everyone in the lab. This means that the students can view my todo list and I can view theirs.

This is a tricky issue probably best sorted out within each lab. However, for us it gave everyone a greater understanding of what we were working on, including letting the students understand more of what a PIs job responsibilities are day to day. For example, students saw that I was working on submitting grant reports or working out a contract and had a better sense of why I seemed busy.

On the other side, I could view the student's todo lists which was helpful for me keeping track of what everyone was working on. Even more helpful was checking that list lined up with our overall lab goals. For example, after a meeting sometimes I have notice that a student will forget something we suggested or interpret the next agenda incorrectly. By being able to see people's working todo lists I had the ability to intervene more quickly to make sure people were on the right path and also avoid people working on things that are not important.

The question of student/postdocs seeing each other's todo list is perhaps a bit more complex. One is could, in theory, create a sense of competition. However, we worked to make sure everyone understood that these todo lists were for personal growth and achievement and not for comparing between people. In addition, different students make more "granular" todo list items, had separate personal todo list management tools, etc... So it wasn't super easy to judge who was working "harder" in any comparative sense (not to mention a wide variety of different stages in the program, etc...)

Regular meetings to check in and provide accountability

In addition to the global todo list, we including regular group meetings where people could check in and discuss any roadblocks they had with one another. These meetings are sometimes known as standup meeting (or daily standups or daily scrums) are short meetings that are held daily in agile programming. The purpose of standup meetings is to provide a quick update on the progress of the team's work and to identify any obstacles that need to be addressed.

Standup meetings are typically held in the morning, and are designed to be brief, with a duration of 15 minutes or less. During the meeting, each team member answers three questions:

What did you do yesterday? What will you do today? Are there any obstacles or issues that need to be addressed? Standup meetings are typically conducted standing up, as the name suggests, to encourage brevity and to keep the meeting focused. The idea is to keep the meeting short and focused on the current work, rather than getting bogged down in discussions or problem-solving.

The purpose of standup meetings is to keep the team informed about what everyone is working on, and to identify and address any issues or roadblocks as soon as possible. They are an important part of the agile process, as they help teams to stay on track and to make progress towards their goals.

Daily registering of goals for the day

Sometime into the first or second sprint, someone suggested that we post to a Slack channel every morning what we planned to do for that day. This was added in for future sprints and was a nice way to add social accountability, especially since each day if you had to come back struggling with the same issue it was apparent:

Multi-week "backoff" periods for more undirected, lower pressure exploration

Finally, a key component of the process was to imagine explore/exploit tradeoffs in research. During the focused sprints, efforts were about clearing a to-do list. However, that often comes at the cost of reading broadly, talking to other students/faculty about wide-ranging ideas, and attending interesting talks/lectures. As a result, we made explicit that in the periods between sprints, people should focus their efforts on learning and undirected exploration while maintaining focus on things that needed to be done.

Results

Well, how did it go? I honestly think it was a success on the whole. I think the most important thing was that people felt a bit more connectedness in the lab, and a sense of common purpose. Students requested we continue the sprints repeatedly over subsequent semesters. In terms of productivity outcomes it was mixed. In some cases the process of research just doesn't lead to punching out a to-do list. Some things take time or are a struggle and the output is not a simple function of the time put in. However, overall I think most people benefitted from metacognitive feedback about how they were spending their time, and the process of planning and checking in on progress. These subjective assessments were backed up by some anonymous surveys we did at one point but they are not so important to the story.

I'd recommend it to any lab that wants to try something new and is willing to be a bit more open about what its members are doing with one another. I'd be curious to hear from other labs that have tried something similar.

I should say that I have a fairly anti-corporatist mindset about academia. I viewed this exercise not as trying to corporatize the lab but more to try to change the way we collaborate and learn together. ↩︎